Think about Functions

What is a Function?

In imperative programming, we often say a function is a sub-module of out program. In order to make our program readable and clean, we often make the repeated parts into functions, then call then in the main part of program with parameters. For example,

1 | |

If we have arbitrary integer a

and want to apply the + 5 arithmetic on a,

we can just use foo(a).

Deep behind this is a “subroutine”,

another piece of code somewhere in memory that will do something to some value on stack,

which is actually divergent from the definition of real “function”.

For example,

1 | |

But how do we interpret the concept of function in math?

Definition of Function

As we know from math class, function is a mapping between two sets of objects (any objects!). Suppose $X$ and $Y$ are sets. If $f$ is a function from $X$ to $Y$, we write $$ f : X \rightarrow Y $$ and denote the element of $Y$ assigned to an element $x \in X$ by $f(x)$.

In Haskell, we can define a function very similar to this.

Let X and Y be sets (types),

a function mapping X to Y is

1 | |

and a function application of x in X is f x (without parenthesis).

From here you can see Haskell is trying it best to make the syntax as close to math as possible.

: is defined as an operator in Haskell,

so we use :: in the function definition.

Note

f :: X -> Yis also called a type signature of a function.- Function is left-associative, so we can ignore the parenthesis when function application, as what Haskell did in its syntax. That is, $fx$ is equivalent to $f(x)$.

Common Functions

As it is defined, function can map anything to anything! Let’s see some typical functions.

Function that Does Nothing

In mathematics, there is a function that does literally nothing.

Definition. An identity function maps anything to itself. That is, forall $x \in A$, function $\mathbb{1} : A \rightarrow A$ is defined as $$ \mathbb{1}(x) = \mathbb{1}x = x. $$ (The first step is a demonstration of the left-associativity).

In Haskell, we have the predefined identity function for generic type a:

1 | |

With the identity function, we can actually define a functional “variable”,

1 | |

Why functional “variable”? In a pure functional language such as Haskell, there is no real variable for the purpose of eliminating side effects. That is, all data is immutable. Many modern languages/tools also have this property, for example, React and Redux.

Fun Knowledge:

in math, we often ose the fancy 1, $\mathbb{1}$ or in $\LaTeX$ \mathbb{1},

to denote the identity.

Why?

There is a saying that

if we define multiplication on the real numbers $\mathbb{R}$,

then 1 is the identity element such that $\forall x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \{0\}$,

$$ 1 \times x = x \times 1 = x. $$

Function on Numbers

This is the most common type of function we learned in math. These functions accompany us from middle all the way to college (or even grad school if you focus on analysis.) These function can be categorized into two major classification: functions defined on $\mathbb{R}$, $ f : \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} $ and those are not, $ f : \mathbb{C} \rightarrow \mathbb{C}. $ (Real Analysis and Complex Analysis are the math course that study the behavior of these functions.)

As for programming, we mostly focus on functions defined on $\mathbb{R}$.

The first imperative example, if we define it as a function, it also falls in this type.

1 | |

These functions can have many interesting property with respect to the set they are acting on. For example, there are different type of sets. There are open and closed set, compact, or connected sets, each having some special structures.

A continuous function on a set preserves the structure of that set. That is, let $f : A \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ be continuous on $A$. If $K \subseteq A$ is compact (or connected, or have other structures), then the set $fK$ is also compact (or connected, or have other structures).

If you are interested in this topic, go find some resources on Real Analysis and basic Topology.Also, I may write blog posts about this in the future.

A permutation is also this kind of function, which is a bijection defined on a set of $n$ distinct elements $S$, $$ p : S \rightarrow S. $$

For more information of permutation, see Permualgebra.

Binary Operations (Composition)

A binary operation on a set $S$ is a function $$ * : S \times S \rightarrow S $$ its mapping is $(a,b) \mapsto a * b$. Here the $\times$ operator is the Cartesian product, where $$ X \times Y = \{ (x,y): x \in X, y \in Y \}. $$

In other words, a binary operations is just some function that takes two inputs and returns one output. For example, addition, multiplication, function composition, are all binary operations.

Discussion: Is division a binary operation?

There is another notation system for functions with more than 1 parameters in math, called Currying, $$ * : S \rightarrow S \rightarrow S, $$ where we see the last set as the output set(type), and the all the sets(types) before it as the input sets(types).

As we define in algebra, addition is $$ + : \mathbb{Z} \times \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}, $$ which can also be express as $$ + : \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}. $$

There is a little difference between this two notation,we will discuss the details in post Introduction to Lambda Calculus.

In haskell, we can define function in the currying way,

1 | |

Note: type Integer in Haskell is an arbitrary precision type

which will hold any number no matter how big,

type Int is the standard int type in computer science.

By the way, Cartesian product itself is a binary operator. Write the definition of Cartesian product in Currying notation, $ \times : X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow (X,Y) $ where $$ X \times Y = \{ (x,y): x \in X, y \in Y \}. $$ we can define it very easily using Haskell list comprehensions.

1 | |

Haskell also support infix operator definition automatically, for example

1 | |

You can also define the function the infix way

1 | |

which is equivalent to the first definition.

If we relate the math symbol with Haskell syntax, where

$\{\} \leftrightarrows$ [],

$:,\leftrightarrows$ |,

$\in,\leftrightarrows$ <-,

then math definition and Haskell code looks exactly the same!

Definition: An identity for a binary operation on set $S$ s an unique element $e \in S$ such that $$ ae = a = ea $$ for all $a \in S$. We often use $\mathbb{1}$ to denote the identity.

Isn’t this definition familiar?

Binary Operation on List

There are two major binary operator of lists. Since there are no lists in real math, I will just write the Haskell type signature.

: is the operator that joint a element and a list of the same type,

and ++ joints two lists of same type.

1 | |

1 | |

Function on Vectors

Recall the idea of vector spaces $\mathbb{R}^n$. The dot product is a binary operation of vectors $$ (\cdot) : \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}. $$

Definition: A function $$T : \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n$$ is a linear transformation or linear operator of $\mathbb{R}^n$ if $$ T(x + y) = Tx + Ty $$ for all $x,y \in \mathbb{R}^n$ and $T(cx) = cTx$ for all $c \in \mathbb{R}, x \in \mathbb{R}^n$.

In this case, a matrix is function!

Definition: Let $T : \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n$ be a linear transformation. Then $T$ is called an orthogonal operator if, $$ Tx \cdot Tx = x \cdot y $$ for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}^n$.

For example, let vector $u \in \mathbb{R}^2$. Then for linear operator $T : \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2$, let $$ T = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix}, $$ then $Tu$ would be the reflection uf $u$ around the x-axis.

A 3-by-3 matrix would be the function that map a 3D vector to another vector in 3D space.

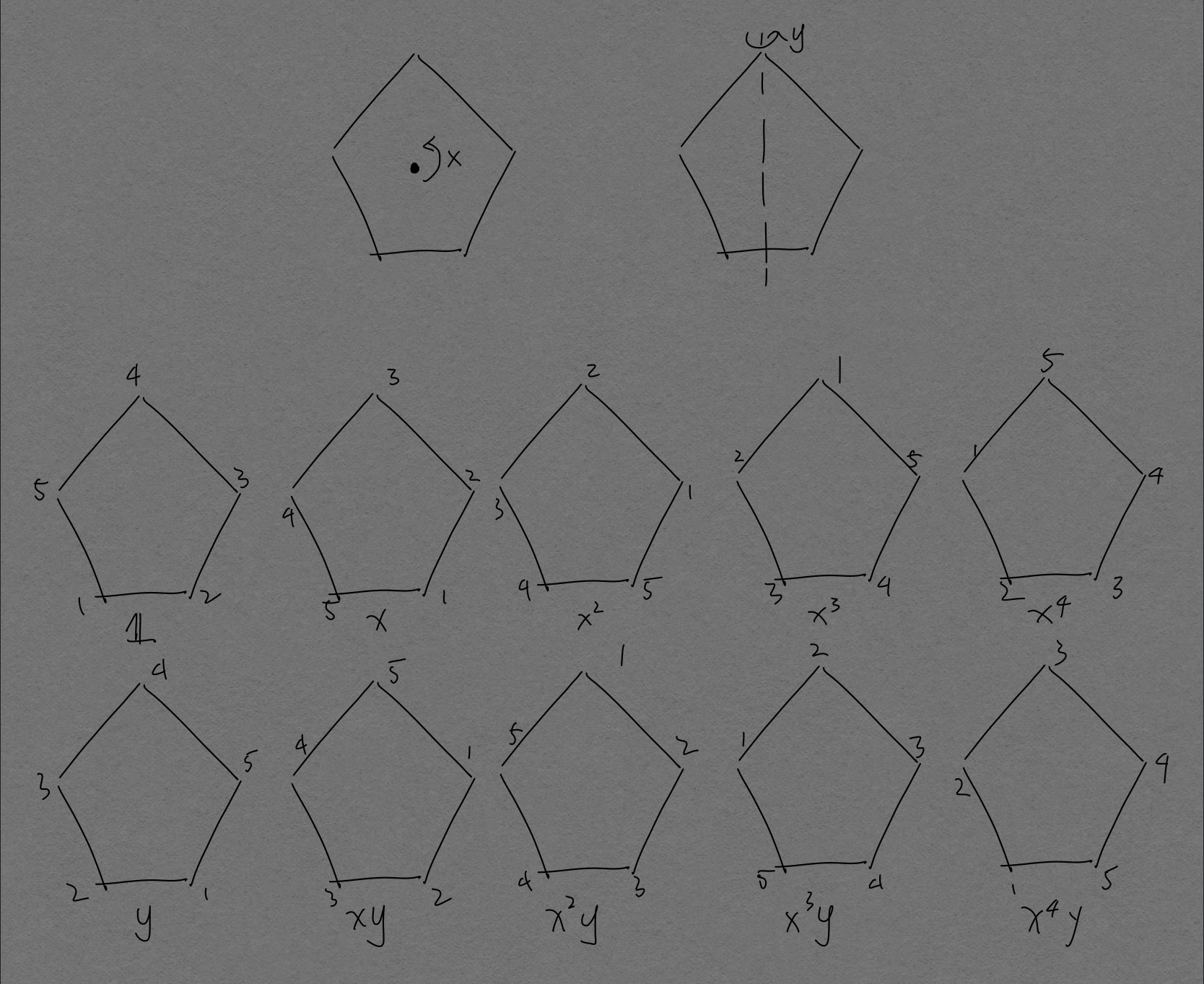

Function on Figure

Function can also act on figures! Consider a right pentagon, number all its angle with number 1 to 5. Define $$ x : Pentagon \rightarrow Pentagon $$ which rotate the pentagon by $2\pi/n$ around its center. Define $$ y : Pentagon \rightarrow Pentagon $$ which rotate the pentagon by $\pi$ about vertical.

Let $x^2$ be the composition of two $x$, then same idea for all $x^n$, $y^n$. Then we notice that

- $x^5$ is the same as $\mathbb{1}$,

- $x^6$ is the same as $x$,

- $y^2$ is the same as $\mathbb{1}$,

- $y^3$ is the same as $y$,

- $yx$ is the same as $x^4y$.

Then we can find the set of all functions of this pentagon, $$ \{ \mathbb{1}, x, x^2, x^3, x^4, y, xy, x^2y, x^3y, x^4y \}. $$

Function on Functions

When we talk about functional programming, there is a feature called function as first-class citizenship. That means function is just data, no difference than other types of data. Therefore, of course we can pass function as parameters and return a function as output.

JavaScript supports this feature as well.

Definition: A higher-order function is a function that either (can be both)

- takes function as input parameter,

- return function as output.

This design is for another true purpose of function programming: reuse the existing functions as much as possible to reduce the complexity of code.

Composition

One great example is the composition operator. Composition is just a binary operation between functions/ Let $A,B,C$ be sets, then $$ \circ : (B \rightarrow C) \rightarrow (A \rightarrow B) \rightarrow (A \rightarrow C) $$ where $f \circ g\ x = f(gx)$. That is, the operator $\circ$ takes a function that map $A$ to $B$ and a function that map $B$ to $C$, then return a function that map $A$ to $C$.

In Haskell, we define the composition operator as

1 | |

Applying Function on List

Haskell also provides other useful higher-order functions.

One is $$ map : (A \rightarrow B) \rightarrow [A] \rightarrow [B]. $$ As this type signature suggests, it takes a function and map $A$ to $B$ and a list $A$, apply this function to all elements of $A$ to get a list of $B$.

1 | |

which runs as

1 | |

Another one is $$ filter : (A \rightarrow Bool) \rightarrow [A] \rightarrow [A] $$ takes two parameters

- a function map from type $A$ to a boolean

- and a list of $A$.

When a function outputs a boolean value,

we can view it as a “condition”.

If the condition is satisfied (i.e. True),

filter takes this value.

In Haskell, filter is defined as

1 | |

1 | |

Using three of them together, we can get

1 | |

All blog follow CC BY-SA 4.0 licenses, please cite the creator when reprinting.